I’ve been waiting for this adaptation for decades…spoilers for both book and film to follow…

I don’t entirely recall the first time I read The Long Walk, the second of seven books written by Stephen King under his Richard Bachman pseudonym. I want to say it was sometime in college, during a period of time where I dove headfirst into the horror genre in its many forms. I do remember being so impressed by the story that it shot into the top of the list of King books I’d loved, and it remains there today, along with Carrie, Dolores Claiborne (if you haven’t listened to the audiobook read by Frances Sternhagen, just stop what you’re doing right now and go find a copy), Storm of the Century (written specifically as a screenplay), and his non-fiction guidebook/autobiography, On Writing.

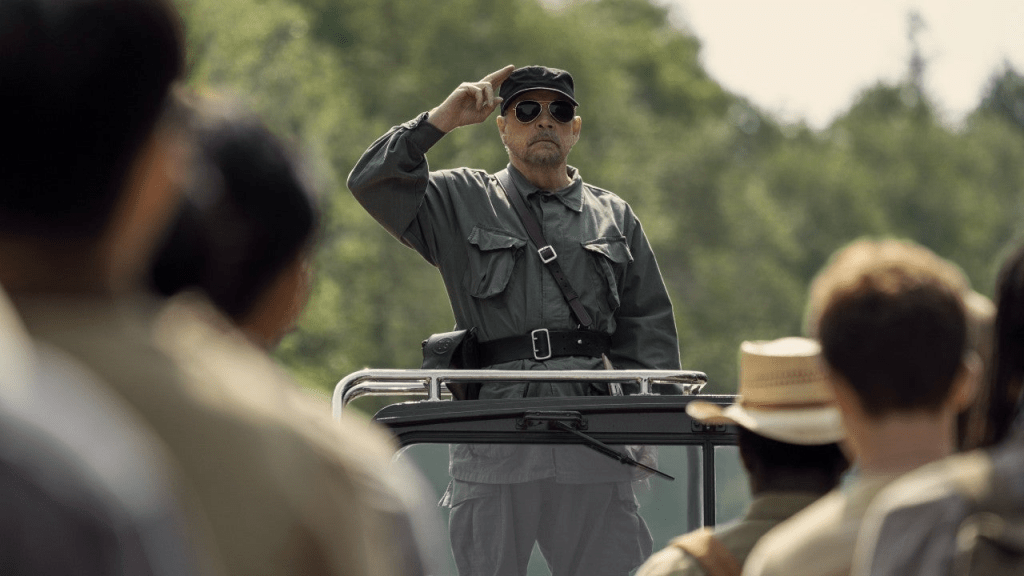

The Long Walk was the first novel King wrote, started sometime during his freshman year at the University of Maine, and it’s a hell of a debut despite not being published until over ten years later, after Carrie, ‘Salem’s Lot, The Shining, and The Stand, as well as the first Bachman book, Rage. Set in a future or alternate totalitarian United States – the book is purposefully unclear about this, although there are references to fifty one states, a date of April 31st, and a German air blitz of the US’s east coast – The Long Walk is an annual contest hosted by the mysterious Major, in which 100 young men and boys are chosen from a random pool of applicants to walk for as long as possible, at a rate no less than 4 miles per hour. Should they fall below this speed, they are given three warnings; after the third warning, the Walker gets a “ticket,” which translates into a bullet in the head. The last one standing is given untold wealth and whatever they want for the rest of their life.

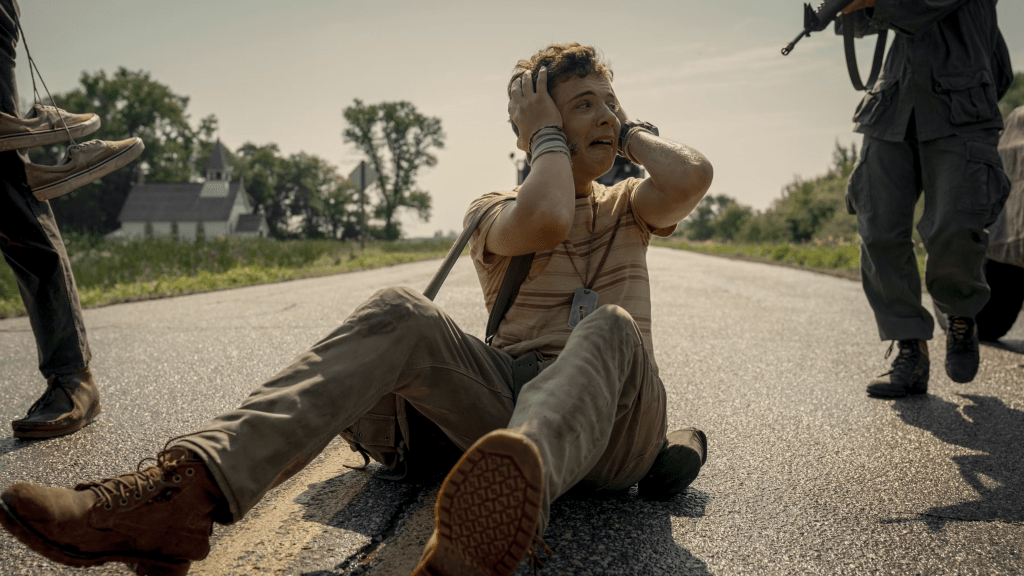

For such a simple premise, the story is rich with psychological horror, particularly after the first Walker gets his ticket and the grave reality of the situation begins to set in. We experience the bulk of the Walk through the eyes of Ray Garraty, a 16-year-old boy from Maine, who is one of a few contestants to have seen a Long Walk before and who has volunteered to participate for reasons that he doesn’t fully understand, although we later discover that his father was taken away by the military for his outspoken political opinions when Ray was a child. Along the way, Garraty develops relationships both friendly and antagonistic with several of the other Walkers, closely bonding with charismatic and compassionate Peter McVries in particular. As other Walkers get their tickets and fall away, the remaining few uncover secrets about themselves and each other, and King does a deft job of building tension while punctuating the Walk with moments of unforgettable horror, including characters being gut-shot, dying of internal hemorrhaging, and tearing out their own throats.

The book ends with Garraty beating out fellow walkers McVries and Stebbins, who had been part of the Walk as a “rabbit” to goad the other Walkers into catching him and who also reveals that he is one of the Major’s many illegitimate children, his goal in winning to be welcomed into his father’s house. Garraty has started to see a dark figure beckoning him to an unseen finish line. At the end of the Walk (which has been estimated at about 460 miles according to this site), the Major congratulates Garraty as the winner, but Garraty unknowingly continues to walk, chasing the dark figure and even breaking into an incomprehensible run, presumably forever until death finally catches up.

There’s already been a lot of analysis of The Long Walk, so I won’t bore you with my own take on it, although I think it largely works as a critique of the Vietnam War. King wisely leaves some details to the readers’ imaginations, especially when it comes to Garraty’s motivations for volunteering for the Walk. The idea of financial security for the rest of your life is surely one reason, and walking sounds simple enough, but at what cost, especially if you’ve already seen a Long Walk before? You’d certainly know how grueling it would be. This is probably the one part of the book that always stuck out a little for me although it never took away from my enjoyment of it. Gratefully, the film adaptation gives us a clearer picture of why Garraty decides to join up. More on that in a bit.

The idea of an adaptation of The Long Walk has been bandied around since the mid- to late 1980s, with George Romero being approached in 1988 to direct it. Later, Frank Darabont, who had directed King adaptations The Shawshank Redemption, The Green Mile, and The Mist, secured the rights with the intent of directing it himself as a weird, low-budget, existential feature. For several years, there had been talk of one company or another developing a film adaptation, including New Line Cinema, before it finally landed at Lionsgate. For myself, I’d wanted to see some kind of screen production of The Long Walk not long after reading it, thinking it might eventually end up as a miniseries if it were going to properly work.

When the feature film version was announced, I was nearly sick with excitement. This was decades in the making, and I hoped that whoever would helm the picture would at least do the story a modicum of justice. Thankfully, director Francis Lawrence (Constantine, The Hunger Games sequels) does a fine job of bringing JT Mollner’s script to life, which condenses the story where needed and emphasizes that this is ultimately a piece driven by the characters and how they relate to themselves and each other. The overall plot is largely unchanged, save for a few tweaks along the way – at the jump, there are only 50 Walkers instead of 100, presumably one from each state. Some of the character details in the book are consolidated as a result, but none of this detracts from the finished product. The ending also differs in a way that I think changes the horror of the original book to something much more grim, especially in our modern political climate.

In the film version, when the Walkers are discussing why they decided to participate in the Long Walk, Garraty (Cooper Hoffman) explains that he joined because he felt like he didn’t have a choice. When chided that the contest is voluntary, he explains that it actually isn’t by implying that the government in charge has been slowly taking away everyone’s rights and ability to make their own decisions in such a way as to force them into things like the Long Walk without realizing they aren’t actually volunteering. He likens it to trapping an animal by slowly boxing it in to a corner or towards one specific path in a maze. Later, we also find out that the Major (Mark Hamill) himself shot Garraty’s father right in front of him and his mother, again for being a political dissident. This punches up Garraty’s reasoning for participating – not only is he worried about his mother being taken care of financially, there’s a retribution aspect that may not have been necessary but adds some dramatic meat to the story’s bones, as his wish should he win is to get one of the carbines the soldiers are carrying throughout the Walk. His initial idea is to shoot the Major on live TV and cause a revolution, but McVries talks him down into just taking the gun to show that maybe the government doesn’t have as much power as everyone thinks.

In the book, as in the film, the final three Walkers are Stebbins, McVries, and Garraty. Where the film deviates is instead of McVries opting to sit down and die in peace, Stebbins going insane and dying suddenly of fatigue, and Garraty winning the Long Walk, Stebbins (who has caught pneumonia) decides to sacrifice himself, leaving McVries and Garraty as the final two. McVries, who is the only other Walker who knows about Garraty’s wish, attempts to stop walking to let Garraty win, but Garraty picks him up from the ground and pushes him ahead down the road. Garraty then collapses on the road and collects his ticket. McVries decides to co-opt Garraty’s wish, but he takes the carbine and kills the Major, then turns and keeps walking into the night. The audience is left to assume what happens next, but most assuredly, McVries doesn’t survive long and we can only hope his violent action causes some kind of positive change. That said, outlook not so good.

On the surface, it seems like a curious shift to McVries’s character, who throughout both the book and the film is largely optimistic, at least as much as one can be in such a time, pushing Garraty along and talking him through some of his darker tendencies with the concept of hope. Despite that, McVries’s decision to kill the Major speaks to something that maybe we in the real world, right now, are not ready to face – that we may not be able to hope our way out of authoritarianism, but rather that violence may indeed be the only way for real progress to happen. If this was the intent of The Long Walk, it’s a truly chilling message, indeed.

The Long Walk (2025)

Director: Francis Lawrence

Screenplay: JT Mollner, based on The Long Walk by Stephen King

Starring: Cooper Hoffman, David Jonsson, Garrett Wareing, Judy Greer, and Mark Hamill

Runtime: 108 minutes